Mapping the Landscape: Paul Sandby’s View near Loch Rannoch

The Landscape in Miniature

Paul Sandby’s View near Loch Rannoch, a drawing dated 1749, is a small work, approximately 17 x 23 cm, so a near miniature.

It is unfinished and far from pristine in condition. Yet, unprepossessing as this all makes it seem, it is an image that has had wide currency, beyond that of far grander examples of the landscape art of the period.

Indeed, it has been reproduced many times, used as a jacket illustration and as a frontispiece, most recently in Old Ways New Roads. Here, I might just say that this was the choice of the designer (who did such a wonderful job on the book), not the editors.

Small in scale but broad in meaning

But, once the suggestion was made, it seemed obvious: it is an arresting and richly associative image, one that makes themes central to the book and exhibition vivid. These include observation and depiction as well as the roles of mapping and improvement in the transformation of the Scottish landscape in the wake of the Jacobite risings. It is for these reasons too that the work is central to the arguments of the first section of the book and exhibition, exploring Scotland as a ‘theatre of war’.

The Military Survey of Scotland

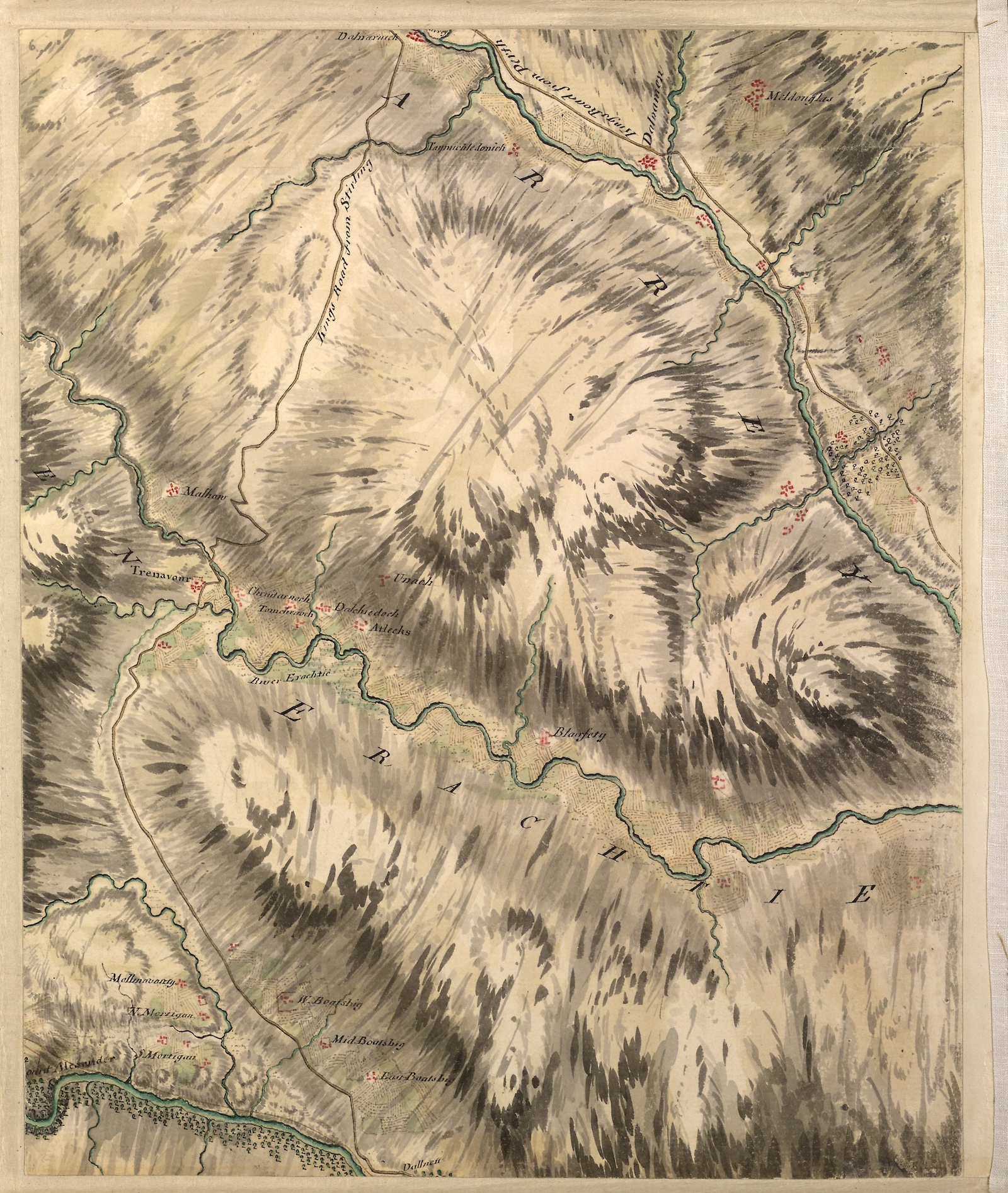

Sandby’s View near Loch Rannoch owes its renown to its connection to the Military Survey of Scotland (or ‘the Great Map’), the large-scale mapping of the country undertaken by the Board of Ordnance shortly after the defeat of the Jacobite cause at Culloden. Examples of the large-scale maps produced by the Survey are at the heart of the opening section of Old Ways New Roads. The project was part of a broader strategy of pacification in the Highlands, alongside the construction of the extensive road network begun some twenty years or so earlier under General Wade (and the starting point of course for Old Ways New Roads).

Showing a surveying party at work in the southern Highlands, Sandby’s drawing is often reproduced in studies of the Military Survey and its chief architects, Colonel David Watson and William Roy. In such studies, the drawing is usually treated as essentially documentary, an on-site record.

View or vision

When first writing about the picture more than ten years ago now, for the exhibition catalogue Paul Sandby: Picturing Britain, I treated it much the same. However, on looking at it again more closely (and it is an image that repays such attention), Sandby’s drawing is less the relatively straightforward matter of fact it is sometimes taken to be (and which I think I first took it to be).

It is something more complex perhaps, as much evaluative as documentary. It is a pictorial appraisal of the potential of the landscape, less a view of how things were and more a matter of what they should or might be.

Map-making

In 1749, the date on a View near Loch Rannoch, Sandby (then just 18) was part of the Ordnance Drawing Room, based in Edinburgh Castle. During the summer months, he accompanied survey parties out in the field. But Sandby’s main role was as ‘chief Draftsman of the fair Plan’, collating field measurements and sketches and undertaking some of the graphic work. While the main engineer and surveyor William Roy probably supplied the fine detail and lettering, Sandby was chiefly responsible for the striking depiction of relief.

Evident in the relief work of the View near Loch Rannoch too, Sandby’s virtuoso painterly style of terrain drawing, in pen and wash, with aligned brushstrokes indicating the direction of slopes and graduation of tones steepness and height, contributed decisively to the artistic and decorative effects of ‘the Great Map’

Mapping the landscape

According to Sandby’s son, Thomas Paul, his father’s time working on the Military Survey of Scotland was “the source of his [later] eminence as a landscape painter”. There, he “saw nature in her wildest form” and acquired “that correct and faithful habit, with which he after viewed and delineated her”. Map-making provided Sandby with a model for expanding the scope of his art, for laying out information about land and life in a particular place as well as its co-ordinates with a wider world. Like maps, works of pictorial art helped plan as well as document change in the landscape.

Commemorating the Military Survey

It is not clear why Sandby produced the View near Loch Rannoch, but it may have been a frontispiece of some sort, commemorating the Military Survey and its achievements. It does seem more emblematic than documentary.

Lined up in a highly formal, symmetrical way, the surveying party appear to be something other than a functional unit engaged in rapid reconnaissance, taking hasty measurements and sightings in an area that had seen a great deal of fighting.

Accompanying the surveyor at the theodolite and escorting redcoats are two Highlanders, local guides, or perhaps interpreters, though their demeanour and dress may suggest otherwise. Striking a standard pose of gentlemanly ease and refinement, one foot forward, hand on hip, the Highlander at far right would seem to have stepped out of a contemporary conversation piece, only one in which a theodolite takes the place of the usual telescope on a terrace overlooking fine parkland.

Scotland’s improvement

That the elegance of the party may be taken as representative of the larger civilising, modernising post-rebellion project of which the Military Survey formed part, also helps explain the presence of the otherwise incongruous female figure, in full formal gown to the far left.

In this sense, it is striking that the measuring chain being dragged by the two figures across the ground are silhouetted against blank paper, in a reminder of the sheets on which the new view of the land being projected was to be inscribed.

Lying on lands confiscated from the Jacobite Robertsons of Struan, Kinloch Rannoch was now under the control of the Westminster-appointed Board of Annexed Estates. The Board’s progressive plans for reshaping the local economy and society included the establishment of a model settlement for discharged soldiers and displaced crofters to be built near this spot.

In all this, we might see Sandby’s View near Loch Rannoch as reflecting on the progressive forces and interests remaking the Scottish landscape at mid-century, on their implications for the place in question. To return to a point made earlier, it is a view of the landscape not so much as it was, but more as it should be.

Loch Rannoch revisited

By way of a conclusion, we might ask what became of the improvements Sandby’s drawing anticipated by turning to what Thomas Pennant had to say about the progress of this landscape some 20 years down the line. Writing of the Board of Annexed Estates, in his pioneering Tour of Scotland, Pennant was approving of the “rare patriotism!” it had shown, notably in its promotion of regular worship, “good government, industry, manufactures, and the principles of loyalty to the present royal line”.

Object

A Highland Dance

Object

A Highland Wedding

Object

A Gillee Wet Feit