“All the World is Travelling to Scotland”: Elizabeth Diggle’s 1788 Journal of a Tour from London to the Highlands of Scotland

by Nigel Leask

“All the world is travelling to Scotland and Ireland” wrote Elizabeth Diggle on 7 July 1788, near the end of her fourteen-week Scottish tour.1 The rise of the ‘home tour’ in the last two decades of the 18th century saw the beginnings of a substantial tourist presence in Scotland, representatives of a newly affluent British middle-class with money and leisure time on their hands. Best-selling publications by earlier 18th century ‘philosophical’ travellers like Thomas Pennant and Dr Johnson had popularised two preferred tourist routes, known as the ‘petit’ and the ‘long’ tour of Scotland, while William Gilpin’s picturesque tour of 1766 (published in 1788–89) promoted the visual appeal of Highland landscapes, especially for middle-class women tourists. Landscape sketching (like diary-keeping and letter-writing) was an expected accomplishment of socially privileged women in the 18th century. Although only four women actually published Scottish tours in the period 1770–1830, Betty Hagglund has listed 55 manuscript tours written by women prior to 1830, certainly an underestimate, especially if one considers numerous tours described in women’s letters and diaries not exclusively focused on travel.2

Elizabeth Diggle’s journal is a 128-page manuscript notebook held in the University of Glasgow’s Archives and Special Collections (MS Gen 738).

It is a fair copy of 32 letters which the author sent home to her family during a 14-week tour in the spring and summer of 1789, before she joined them at their holiday residence at Margate at the end of her travels. Although the early and later letters describe her journey through England, the Scottish letters are numbered 8 to 23, comprising about two-thirds of the whole journal. As we’ll see, there was an element of serendipity (rather than advance planning) in Diggle’s Scottish tour. The model ‘itinerary’ she included at the end of her journal represents an idealised version of the ‘clockwise petit tour’ of Scotland, looping north and west from Glasgow via the military roads through Argyll and Perthshire, before returning to Edinburgh: in fact this reversed the actual course of her tour. Her ‘itinerary’ lists all her stages, with distances travelled between each, and a ‘Tripadviser’-style commentary on each inn she stayed in. Luss is rated “very bad”, whereas the “new inn” at Arrochar is “very good”. (Durie p. 29).

Little is known about Elizabeth Diggle herself, except that she was an affluent, middle-aged, unmarried women, residing in the seaside town of Broadstairs in Kent. She was evidently well connected with the gentry, carrying letters of introduction to some of the great and good in both England and Scotland. Touring offered Georgian women freedom from the restrictions of matrimony or domestic life, and it’s interesting how many of the surviving written accounts of this period are the work of widows, childless women, or divorcees: in this respect Diggle resembles Dorothy Wordsworth, Sarah Murray of Kensington, Elizabeth Spence, and Sarah Hazlitt.3 Diggle travelled in a covered chaise accompanied by her aunt, driven by her coachman Joseph. Teams of horses were hired and replaced at coaching inns en route (except for in the West Highlands where they were few and far-between). Unlike other travellers, Diggle doesn’t tell us much about her travelling ‘knick-knacks’,4 although she does evoke the wear and tear of 14 weeks travel: “My hat is faded to pieces, my coat pinched, ink’d & the carriage all faded, Joseph’s jacket turned into a brown one & so we make as shabby a figure as need be” (Durie, p. 36). Unlike Hester Piozzi, who toured Scotland a year after Diggle, or Sarah Murray of Kensington, indomitable author of the best-selling Companion and Useful Guide to Scotland (1799), Diggle wasn’t especially interested in picturesque descriptions of Scottish scenery, although she did describe sketching at Loch Leven Castle (Durie p. 24). However, her tour is distinguished (in her own words) by the “exactness & prolixity” of its description of Scottish people and places: even if she felt she’d met her match in James Boswell, whose Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (1785) she consulted at Hamilton, on the return lap of her tour (Durie p. 34).

A traveller’s account of their motives for undertaking a tour usually offers insight into the experiences they describe. Although Elizabeth Diggle was enjoying an extended holiday in Scotland, her immediate pretext was to attend a family wedding at Murthly Castle in Perthshire, which provided a base for the first half of her Scottish sojourn. Frustratingly, she provides only initials rather than names, but my research suggests that she was a guest of Sir John Stewart, 16th Laird of Grantully and 4th Baronet of Murthly and Blair (1726–1797),5 whose daughter Grizel married Rev William Buckle, Rector of Pyrton, near Oxford, around this time. It’s possible that Buckle was Diggle’s relative. This wedding exemplifies the high rate of intermarriage between members of the Scottish (here Highland) gentry and nobility and the English upper or middle classes in this period of ‘consolidating Britishness’, facilitated by the fact that the Stewarts of Grantully were Episcopalians (with a strong Jacobite lineage), rather than Presbyterians.

Time will only permit a few highlights of Diggle’s tour, but I’ll start with her very characteristic ‘first impression’ of Scotland. At Dunbar, the first Scottish town she arrived in she described “women…without shoes & stockings & hats or bonnets, giving one in the latter respect and idea of France” (Durie p. 21). After putting up at Walker’s Hotel in Edinburgh, the party toured the sites of this “finest city in Europe” (Durie p. 37), especially Holyrood Palace, where she indulged her interest in Mary Queen of Scots, as well as visiting the Botanic Gardens and natural history museum, “thro’ the politeness of Dr [John] Walker” (p. 23). After dining with the banker Sir William Forbes of Pitsligo and attending the theatre, Diggle wrote to her sister, charmingly:

“I am as stupid as an owl, & I’ll tell you why, I have seen so many new people & things within this week, that they are all in my head pell mell, a castle upon a lady of quality, & a scotch bonnet upon a church etc etc the young ladies here in general draw & paint & are much accomplished. They have all fine teeth & are taller than you & I.” (Durie p.22).

Diggle and her aunt arrived at 15th-century Murthly Castle around 18 May, where they joined the pre-nuptial house party, boasting that she had gained “great credit” for her reel dancing in the evenings, after rambling in the beautiful grounds during the day. Around 19 May they visited beauty spots along the river Braan, where Sir John Stewart’s estates bordered those of the Duke of Atholl: here Diggle gave a memorable description of the Duke’s ‘Ossian’s Hall’ near Dunkeld, which she described as “a fairy palace”:

“the entrance is by a rude gothic porch, a painting of the blind bard Ossian being the only figure that strikes the eye, he disappears at the touch of an invisible spring, & you are introduced to a most elegant room adorned in the most improved style of modern art. I conceive that both these apartments are meant as emblematic of the ancient & modern times. But I had too little time upon the spot, & too much subject for thought, to endeavour to trace the justness of the idea by observing the ornaments more particularly.” (Durie pp. 25-6).

William Byrne after George Walker, ‘Ossian’s Hall, Dunkeld’, engraving, 1803

Writing from Perth to her sister at Margate on 27 May following the wedding, Diggle reported that “Miss Si is married” and was now (as “Mrs B”) en route for London (presumably Grizel Stewart, now Mrs Buckle?): “we were really happy at Murthly, but it must be dull now; for the graces M: G: & H are flown” (p.26). They were shortly to return to Murthly, however, on the invitation of Sir John. Having suffered a bout of ill-health, Diggle decided to use it as a base for gentle excursions to Scone Palace, Castle Duplin, and Dunkeld while she convalesced. After her recovery, the tourists decided to “tack on a new tour to our old one, & go further north”, or (as she put it) “making the long tour instead of the short” (p. 28) travelling to Inverness via Aberdeen, hiring horses at Perth for a month, with a view to returning to Edinburgh in time for the races on 21 July. Clearly ill-health didn’t affect Diggle’s appetite, as she reported dining in Montrose on “two boiled chicks, a pigeon pie, asparagus, partons [crabs], an epergne of nice sweetmeats…for one shilling and fourpence”! (pp. 28-9).

Deciding instead to follow the course of the ‘petit tour’ through Perthshire to Argyll, Diggle and her aunt were joined “for fear of the bad roads” by “Mr S”, a redoubtable local Perthshire worthy, Robert Stewart of Garth. Fear Ghart (to give his Gaelic title) was a recently-widowed Highland chieftain of the old stamp, to whom they had been introduced at Murthly, accompanied by his 20 year old son, David, an ensign in the Black Watch.6

Notwithstanding Stewart senior’s local knowledge, Diggle’s chaise had a nasty accident on the road to Blair. Undeterred, after admiring the Duke of Atholl’s rhubarb plantations, they continued on to Taymouth, full of summer tourists who had come “to drink goat’s whey” (p. 27). Diggle enthused “here we are in the heart of the highlands, I am quite in love with them & shall never like to live near London…any more” (p. 30).

![Illustration - [William Byrne after George Walker, 'Taymouth', engraving[AD3] , 1803] - c4.6](https://oldwaysnewroads.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2-Taymouth-1-fixed.jpg)

Illustration – [William Byrne after George Walker, ‘Taymouth’, engraving[AD3] , 1803] – c4.6

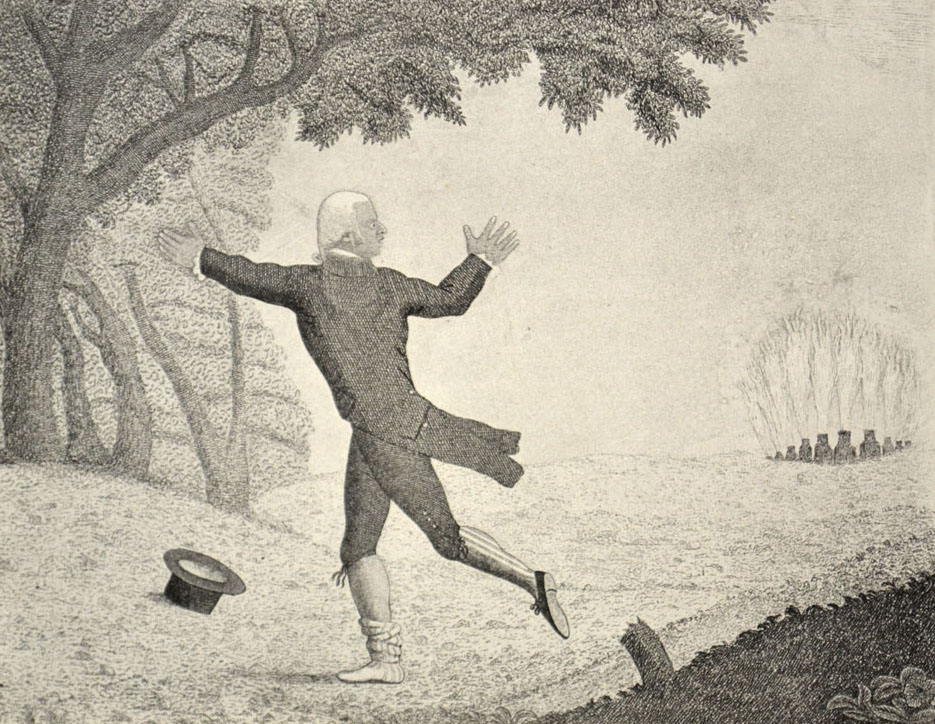

Putting up in the Duke of Argyll’s ‘New Inn’ at Arrochar, they visited Rosneath, the Gair Loch and Loch Lomond, before returning south to Glasgow. Here, their lodgings in the Tontine Inn on Argyll Street were “as big as a castle, & Glasgow is a bustle enough to frighten us poor highlanders”, although they duly visited the College and Cathedral (pp. 31-2). They had decided to occupy the time before the Edinburgh Races on 21 July by returning to the ‘New Inn’ at Arrochar for a further ten-day stay, despite deteriorating weather. But in the meantime, they visited a Glasgow “inkle [or ribbon] factory” where Diggle was impressed by the machinery (“one pull moves a great number of shuttles, weaving so many pieces of tape at the same instan”) and the dexterity of the women and girl workers, who “fold the pieces of tape & bobbins into the neat forms we see them at the shops” (p. 32) The industrial theme reminds us that 18th century tourists visited factories and mines as well as beauty spots and historical monuments. She also provided a fine description of a visit to the Carron Iron Works near Falkirk (“the dominion of Vulcan”) in a letter of 26 June:

“Heavens! We are escaped from the infernal regions…a whole town of smoke & fire, & a thousand people at work, furnaces blazing on all sides, half seen through a black smoke, beings whose appearance I leave it to you to imagine, pouring liquid fire into caldrons, hammering red hot iron, etc. & and an engine working that absolutely overpowered me by a louder voice than ever I had heard before…” (p. 32).

Illustration – [John Kay, Copper bottom’s retreat, or a view of Carron Work!!!, engraving

The final section of Diggle’s Journal describes visits to Hamilton Palace, the Falls of Clyde, and the “magnificent but miserably neglected palace like house of Drumlanrig, the Duke of Queensbury’s, who has visited it but twice…the furniture and everything about it appears at least a hundred years old” (p. 35). Their last view of Scotland was of the inn at Gretna Green “for the reception of future matrimonial pairs”, which is an appropriate closing note for a tour that was planned around a wedding, albeit of a more respectable kind. Crossing the border to Carlisle on 7 July, Diggle closed the Scottish section of her tour with the memorable words: “We have now bid adieu to Scotland, oatcake & naked feet. All the world is travelling to Scotland and Ireland” (p. 36). And so closes the Scottish section of this remarkable tour, which casts considerable light on the day to day realities of travel, as well as representing an intelligent female commentator’s perspective on the ‘old ways and new roads’ of late-18th century Scotland.

- All quotations from Diggle are from the sections of her journal published in Alastair J. Durie, ed., Travels in Scotland 1788-1881. A Selection from Contemporary Travel Journals, (Boydell Press: Scottish History Society, 2012), pp. 18-40, p. 36. (Hereafter Durie in text). It has never been digitised or fully transcribed.

- Betty Hagglund, Tourists and Travellers: Women’s Non-Fictional Writing about Scotland, 1770-1830, (Bristol, Buffalo, Toronto: Channel View Publications, 2010), pp.18-19. See also Kinsley, Zoe, Women Writing the Home Tour, 1682-1812 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008). For a selection of newly edited manuscript tours of Scotland by women, see Curious Travellers website: https://editions.curioustravellers.ac.uk/tours.

- See Nigel Leask, Stepping Westward: Writing the Highland Tour, 1720-1830 (Oxford University Press, 2020), pp. 187-217.

- Link to Viccy Coltman’s talk

- It was Sir John’s grandson, Sir William Drummond Stewart (1795-1871) who really put the family ‘on the map’, as a celebrity adventurer in the Rocky Mountains. See William Benemann, Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012).

- General David Stewart went on to become a Napoleonic War hero, friend of Sir Walter Scott, and author of Sketches of the Highlanders of Scotland (1822), in which he criticised the Clearance policies of his fellow Highland landowners.

Object

Isle of Staffa

Object

Fingalls Cave