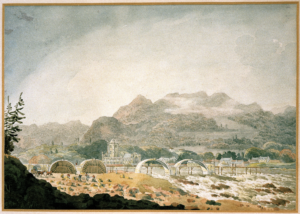

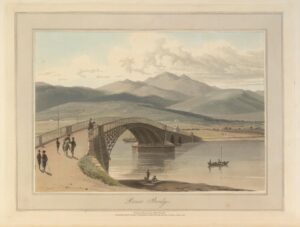

George Heriot, The Building of Telford’s Bridge at Dunkeld, Perthshire, 1806, watercolour, Historic Environment Scotland

The scarcity alone of images portraying the mechanics of road and bridge building in the Highlands make this little-known drawing worthy of our attention. But, at the risk of attaching undue weight and consequence to a drawing of apparently modest intent, of a kind that is usually treated as merely illustrative, it is a picture that condenses a remarkable array of historical and topical allusion, affording a commentary of sorts on the wider cultural and technological ambitions Telford’s bridge represented. It is a drawing of a precise moment as well as a particular place. Yet, in the circumstances of its making as well as its imagery, Heriot’s picture allows us to review the broad range of social forces and relations that combined to remake Scotland’s localities and spur the inter-related practices of landscape art and travel.

Selecting a broad strait of the river, a little way above the cathedral city’s historic lower ferry crossing, Telford’s choice of site was as politically savvy as it was practical. Mindful of its potential benefits to the local economy and helping to stake the project out as an extension of landed power, the owner of the Dunkeld estate the Duke of Atholl was to take an active role in the building of the bridge and lay out of ‘the improved lines of road . . . proposed to be made on each side of the river’.[i] Seven spans across and stretching for nearly seven-hundred feet, the bridge was an ambitious and costly undertaking. On the announcement of a significant shortfall in the government’s budgeting for the project, the duke pledged to make up the difference on the condition that he could then levy a toll on the crossing to recoup his investment. A complex mix of scenographic and economic concerns framed these plans, the path of the new road that the bridge was to carry being plotted in such a way as to connect a sequence of landmark sites on the tourist trail. In Telford’s own words, the route would open an ‘extensive prospect of the Tay valley . . . and other romantic scenery’ as well as facilitating better access to ‘the waterfalls of the Tummell, the wilds of Rannoch, and all the peculiar features of the Central Highlands’.[ii]

Having served in the military and as a government official during extended sojourns in the Caribbean sugar islands and colonial North America, travel was a defining feature of Heriot’s art and biography.[iii] Of East Lothian minor gentry stock, and a former protégé of the Scottish Maecenas Sir James Grant, Heriot also had considerable cultural ambitions, keeping up a reputation as a gentleman amateur, learned in the study of natural history and the polite arts. Making the long voyage home from across the Atlantic, Heriot spent the last months of 1806 touring and sketching his native landscape. This saw him produce a series of views of Scottish river scenery, which as a group traced the country’s progress through its landmark bridges, from the historic, storied structure spanning the Forth at Stirling to the succession of grand designs erected over the last century on the banks of the Tay, at Aberfeldy, Perth and now Dunkeld. Finely observed and highly developed as compositions, the drawings may have formed part of tentative plans for an old-world, comparative companion-piece to the pioneering account of ‘the picturesque scenery’ of the Saint Lawrence river that Hariot was to publish the following year as Travels through the Canadas.

George Heriot, Bridge at Stirling, Glasgow Museums

Of some accomplishment, Heriot’s watercolours reflected his military training as well as a familiarity with the compositional grids and procedures of the picturesque. Twenty years earlier Heriot had been a cadet at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, where learning to draw was part of the curriculum. Guided by the Chief Drawing Master at Woolwich, Paul Sandby, whose early work for the Ordnance had recommended him to the post, Heriot had been taught the methods ‘of describing the various Kinds of Ground, with its Inequalities, as necessary for the drawing of Plans; [and] the taking of Views from Nature’ that his tutor had first developed when employed on the Military Survey of Scotland.[iv] Sketching the landscape, according to one of the course guides, brought ‘the eye to the knowledge of it’.[v] Students sharpened their vision with a sketchbook. While the social prestige of drawing as a polite accomplishment doubtless appealed to Heriot, as in keeping with his gentlemanly self-image, this idea of the art as a practical means to interrogate and better understand the distinctive character of a terrain was not lost on him either. Having already applied Sandby’s lessons in the field to the landscapes of colonial Canada, in a sense, his sketches made of places along the Clyde and the Tay brought them back home, to the source of his tutor’s ‘particular style’.[vi] Like his former drawing master, Heriot had a keen eye for a world in transition, where work, leisure and social encounters took place against a backdrop of parks and forests, antiquities, townscapes, and natural wonders. Such are the concerns that animate the view of the bridge-building process at Dunkeld.

Novel as that drawing may appear, it stands in a well-established pictorial tradition. Bridge-building projects on the Thames had been good-sellers for Sandby’s London art-world contemporaries Canaletto and Samuel Scott as well as his regular collaborator Edward Rooker.[vii] Such images dramatized the processes of bridge building as spectacles of technological innovation. Transferring the urban narratives of such precedents to rural Scotland, Heriot’s Dunkeld scene rather amplifies the drama. Framed by the branches of a decorative larch, which may allude to the ducal plantations across the way or else the role the wood had in the building of the bridge, the stretch of gravel deposit along the southern riverbank is littered with anecdotal, picturesque detail, most notably a party of labourers dressing locally quarried sandstone. Cutting back across the picture-plane is a temporary wooden pont that shadows the masonry piers and arches already in place. All of this finely observed incident leads the viewer neatly through the construction process. But the artist’s concerns were not narrowly documentary. There is something poetic perhaps about the contrast between the everyday mundanity of the labourers’ toil and the epic grandeur of the situation. Moreover, setting the Gothic arches of the cathedral in startling conjunction with those of the bridge taking shape before them, the drawing explores the play of past and present in the making of this landscape.

Others were to cast Telford’s improvements to the country’s infrastructure in a scenic light; William Daniell, for one, took delight in the stark contrast between the slender lattice ironwork structure that carried the Great North Road across the Kyle ofSutherland at Bonar Bridge and the bare expanses of the surrounding hillsides.

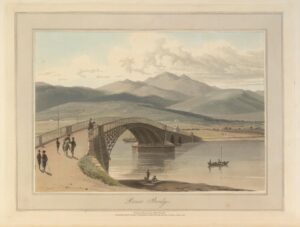

William Daniell, Bonar Bridge, c.1814, aquatint in A Voyage Round the North and North West Coast of Scotland, and the Adjacent Islands [1820] , Alamy, British Library Board

Such images are rarely so poignant as Heriot’s drawing, however. On one hand, as it reflects on what was about to be swept away, Heriot’s Dunkeld scene strikes a melancholic note. Telford’s grand designs saw buildings pulled down, roads re-directed, and the river dammed. On the other, the drawing pays homage to the forces galvanising this local landscape, that combination of civic, commercial, and landed interests that were driving projects like the Dunkeld bridge development at a local and national level. More to the point, it is an image of the landscape that, in the artist’s biography and in the conditions around its making as much as its subject-matter, brings together several notable tensions in the early nineteenth-century picturing of land and life in Scotland. The work of a lowland Scot, training his military-educated eye and skill as a draughtsman on the transformation of the highlands on a tour of his own country, Heriot’s drawing exemplifies just some of the complex exchanges and interactions that had gone into making Scottish scenery the subject of landscape art.