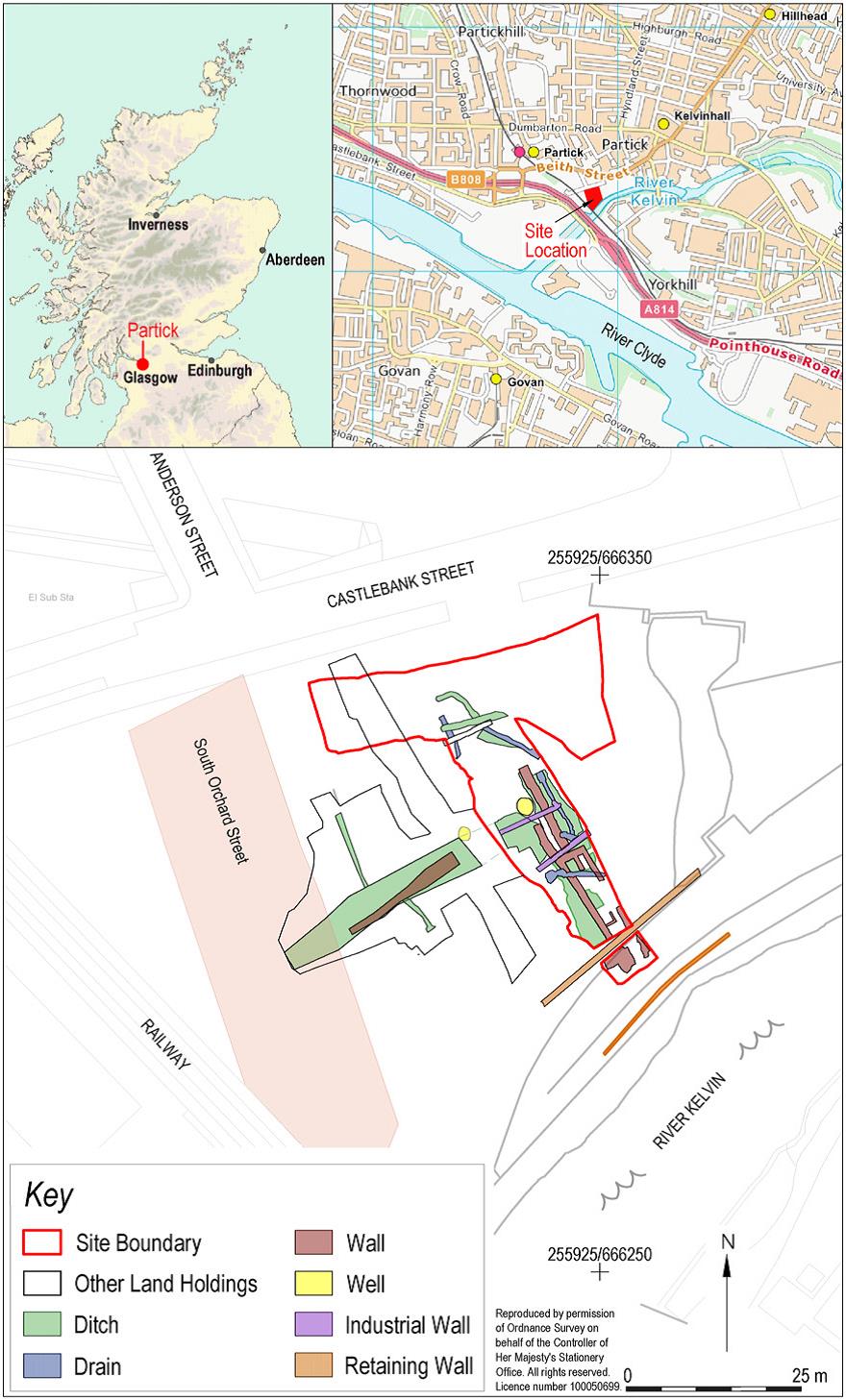

A Partick-ular Castle – but why did it disappear?

Stirling – Edinburgh – Bothwell, “that one in the Highlander/ Outlander film”*… We all know what castles ‘should’ look like. They’re balanced on a clifftop, with high walls, towers, and a moat, even if they’re in ruins … But how did we get this idea of a ‘proper’ castle?

This is a quick guide to the Glasgow castle you’ve never heard of. Partick Castle (yes, honestly) was a very small tower house, so-called because the rooms were piled on top of each other, linked by a spiral staircase. This was a medieval style and easily defended, but Partick was built in 1611, when the country was more peaceful. In less than 100 years, tall, dark narrow towers with tiny windows were seen as too uncomfortable. After 1700, many wealthy Glasgow merchants owned plantations in Britain’s American and Caribbean colonies. They used enslaved African labourers, to grow sugar and tobacco, and spent part of their enormous profits on ‘classical’ mansions around Glasgow. These had modern rooms laid out horizontally, with large windows and gardens. The house at Partick was considered old fashioned and undesirable.

The clichéd tourist view of a grand Scottish fortress – Stirling Castle. © Historic Environment Scotland.

What did the castle look like?

The tower house was built by George Hutcheson (c1560-1639), a successful lawyer who made a fortune by selling land on behalf of Glasgow town council and founded Hutcheson’s Grammar School. His detailed instructions to the castle stonemason still survive.

George Hutcheson’s statue, on Hutcheson’s Hall, Ingram Street. © Morag Cross.

It was a small but prestigious gentleman’s quiet country retreat, situated on the riverbank where the Kelvin meets the Clyde. Lawyers accumulate paperwork, so he had a study, overlooking the front door, built-in cupboards and wood-panelled walls. Hutcheson even used his own shoe-size to pace out the room sizes, so we know the vaulted kitchen was about 14ft square. A spiral staircase beside the main door led to the ‘great hall’ or main reception room, on the first floor. This had three long windows facing east, towards the town, as well as a private parlour or living room. The house went rapidly ‘downmarket’ in the 18th century, the grounds were used to bleach newly-woven linen, and the hall became a pub.

Robert Paul, A View of the banks of Clyde taken from York Hill, 1758, hand coloured engraving, GLAHA:17700. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow. This engraving shows the castle grounds, highlighted yellow, where the Kelvin (right) joins the Clyde, with Govan among the trees, c.1758.

Partick – a peaceful country village

Partick and Govan, both just peaceful rural hamlets, were linked by a ferry across the Clyde. Anyone travelling north to Glasgow, Stirling or Dumbarton had to cross the river either at Glasgow Bridge, or by the ferry landing close to the castle. After the Jacobite uprisings were crushed in 1746, the British government laid out new roads (eventually creating Ordnance Survey maps), leading to the military garrisons across the Highlands. Curious travellers ventured along these routes into the previously ‘wild’ north, revealing dramatic, mountainous landscapes with castles large and small guarding passes and glens. Among them were Tyram, Duirt and ‘Elan Stalker’, all sites represented in Old Ways New Roads online. Partick, described by one owner as ‘a little country dwelling near Glasgow’, was much the same shape as those fortresses, but it stood in an unremarkable flat field, ringed by trees.

Andrew MacGeorge, View of Partick Castle, looking southwest across the Kelvin, 1828, lithograph. It includes Govan Parish Church spire in the background and Water Row in the centre. The ruined great hall windows are hidden by the trees. (The view is reproduced as an illustration in Laurence Hill, ‘Huchesonia’, 1855).

Around 1784, the owner (who lived in another much grander tower house at Castlemilk), removed the roof to re-use the wood in neighbouring Merkland Farm-house. Overnight, this made the dilapidated castle look like an ancient pile of stone, and urban myths soon spread that it was ‘the Bishop’s Palace’. The medieval bishops of Glasgow did indeed have a small manor or farm there (possibly resembling Provan Hall), but it was probably demolished around 1500.

Pictures of a lost castle

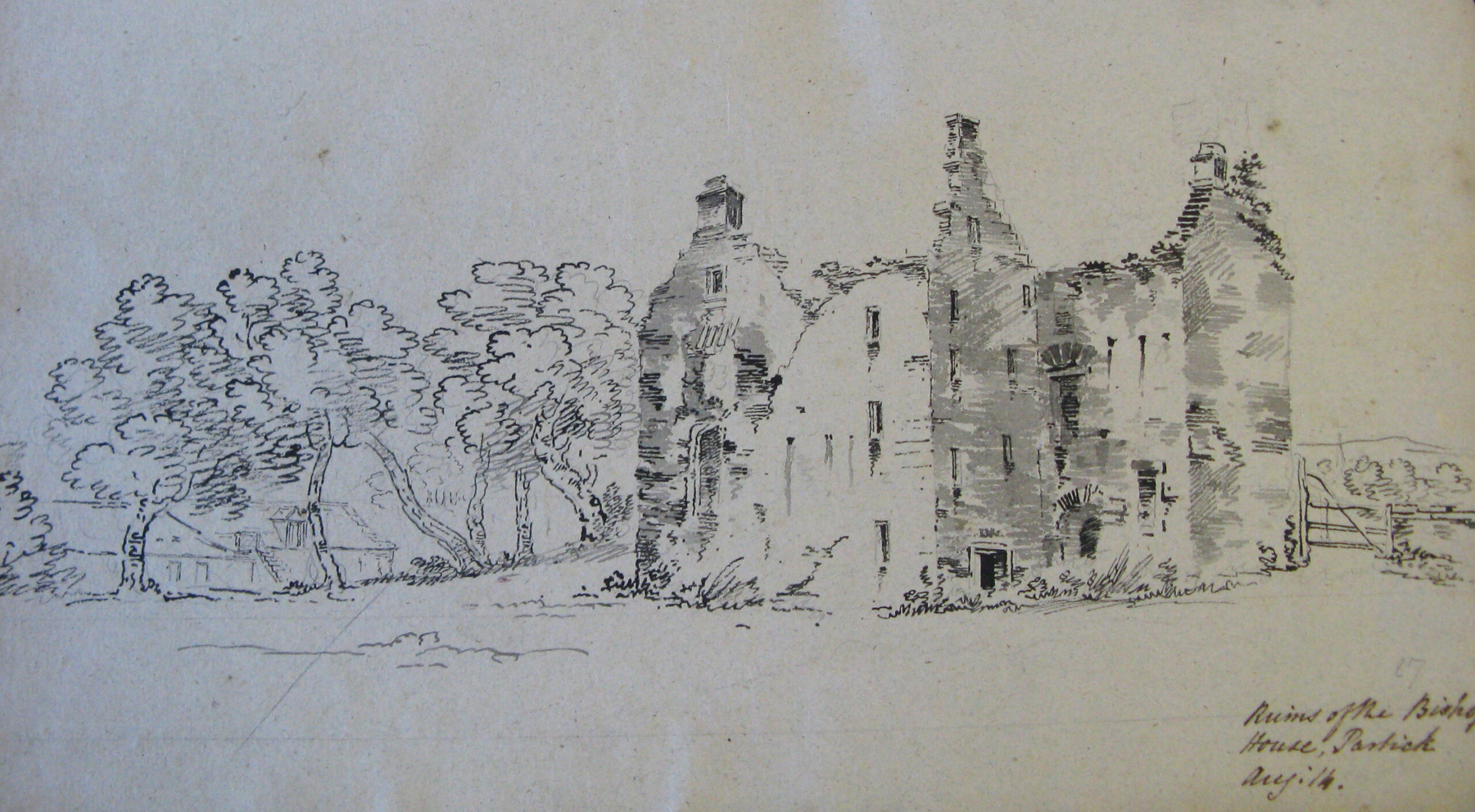

This ‘new ruin’ was now a suitable subject for local artists and those on their way to Loch Lomond and beyond. The rapid pencil drawing was made in 1799 by John Claude Nattes, a refugee from the French Revolution (escaping conflict isn’t just a modern experience). By calling it ‘the Bishop’s House’, he shows that he thought the building was much older than it really was. ‘Fake news’ existed back then too. Nattes was acting like a ‘human camera’, making on-the-spot illustrations for a guidebook to Scotland. 18th century artists described this as ‘taking a picture’, and we still say ‘taking a photo’, although we now use mobile phones. Nattes has included an ordinary field gate, as the castle was now surrounded by a busy working farm.

Jean Claude Nattes, View looking south east, pen, ink and wash drawing 1799. MSS.5203, f.64. © National Library of Scotland.

The gate shows the everyday agricultural background.

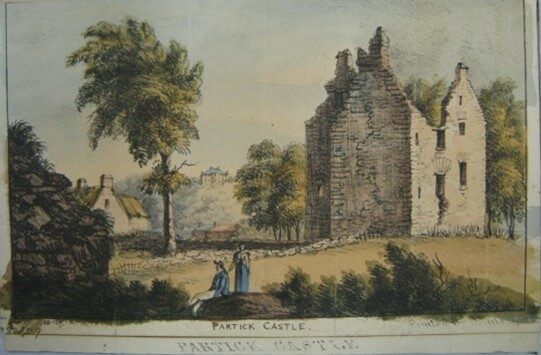

The transformation of Scotland as a rugged, remote and thrilling – but safe – tourist destination in the early 19th century, coincided with an artistic fashion dubbed ‘the picturesque’. Designers laid out gardens and stately homes to look like natural landscapes, although every tree was carefully chosen, and the ponds were artificial. Paintings of gloomy fortresses in forests were in style, but Partick lacked all the ‘typical’ features that made other castles more famous. It was never designed to keep enemies out, but to be a rich man’s second home, without a drawbridge or arrow slits.

A picture with a mystery

The next image has a strange story – it was found inside a time-capsule buried in 1824, under a city-centre police station. The picture had been wrapped around some coins, and was recovered during modernisation in 1907. It had just been used as scrap-paper, and not because it showed a local attraction. The house in the distance is Yorkhill, where the hospital now stands. The curator of the People’s Palace was the police superintendent’s brother, and so this unique print was donated to that museum.

Anonymous, Partick Castle, hand coloured print. © Glasgow Museums Collection. Here the artist is looking northeast, and includes Merkland Farm to the left, Yorkhill in the centre, while the Clyde is ‘offscreen’ to the right.

Before the shipyards!

The final picture is a watercolour of 1825-30, by art teacher John Gilfillan, looking from the west. He may have included a self-portrait, sitting in his top hat beside a female student or relative. The tower has been quarried for building stones, making it look even older, and yet the housewife hanging out her washing emphasises the contrast between ‘the olden days’ and ‘everyday modern life’.

John Gilfillan, Partick Castle, watercolour, c 1824. © Glasgow Museums Collection.

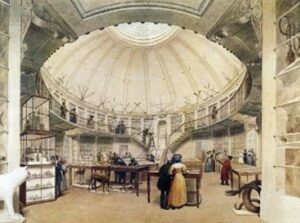

Gilfillan also painted the interior of Anderson’s College Museum in Glasgow, and later emigrated to New Zealand, where his family were killed in conflicts between Maoris and European settlers. His best-known painting, showing Captain Cook ‘claiming’ Australia for Britain, is now controversial because it ignores all the rights of the Aboriginal inhabitants.

John Gilfillan, The Dome of the Andersonian Museum in George St, now part of Strathclyde University, c.1831. Ref OP 2/1/14. © Strathclyde University Archives.

If it had resembled a ‘real’ castle, and its location was more spectacular, would this tower have been more valued and protected? Sitting in a busy working farmyard, it was knocked down in 1836 and the masonry built into walls on Merkland Farm. Even the name ‘Castlebank Street’ is called after a later mansion, and doesn’t directly refer to the tower-house itself.

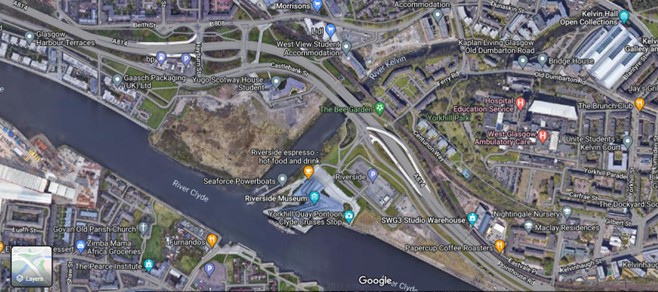

Satellite map of area today.

‘New roads’ lined with ship-builders’ tenements meant that there was no practical use for the ‘old ways’ of living recalled in the roofless monument, and it was carted away. Now, we can only visit Partick Castle through pictures on paper, and in the new technology of internet exhibitions like this one.