Illustrating Scotland’s Antiquities

In 2019 I had the opportunity to become a Hunterian intern while studying for my MSc in Museum Studies at the University of Glasgow. The internship saw me working for the ‘Old Ways New Roads: Travels in Scotland 1720-1832’ exhibition. I spent most of my time studying and cataloguing old and rare illustrated publications, as well as ephemera held at the University of Glasgow Library Archive and Special Collections. The aim was to identify 18th– and early 19th–century publications and manuscripts related to the experience of travel in Scotland, looking for visually interesting material for the exhibition. By the end of the internship, I had created a detailed catalogue of illustrations found in more than 50 different book titles. The material examined was diverse, encompassing pastoral verse and epic literature, travel accounts, satirical poetry and military treatises as well as scientific and antiquarian writing. It is no exaggeration to suggest that the richness of this literary world would require an exhibition of its own to be fully appreciated. In this blog, I will present some of my favourite publications which, by no accident, fall under a common theme; the depiction of Scottish antiquities.

As a non-Scottish student recently moved to Glasgow, I had the opportunity to learn about Scotland’s past just as I was exploring its present. However, as an archaeologist passionate about the classical world, I also had the opportunity to take a peek into the way Scotland appropriated the classical heritage following the Act of Union while rediscovering its own unique identity. Parallels were drawn between Edinburgh and Athens, Ossian and Homer, while many believed that a superior Scottish culture could conquer the English in the same way that the Greeks had conquered the Romans with their culture (Lowrey 2001, 150).

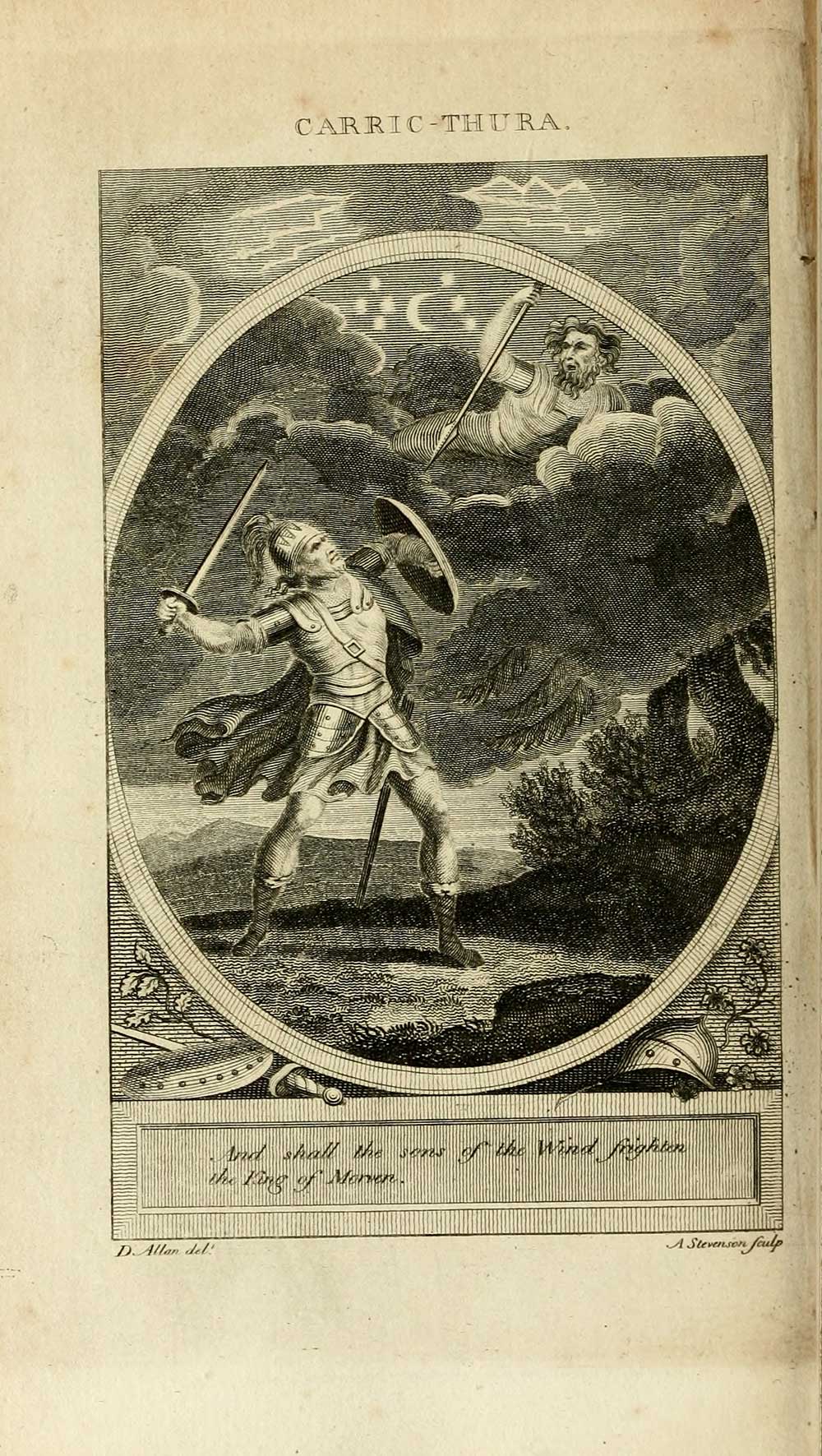

In David Allan’s Plates to Illustrate the Poems of Ossian (1797) one can clearly see the artist using visual references drawn from Greek as well as Norse mythology and art. Another key component of the time was the cult-like fascination with ruins and antiquities. Already before Thomas Pennant’s A Tour in Scotland (1774 and 1776) tourists had begun travelling to Scotland to experience the beauty of the natural landscape (the picturesque) and its history (antiquities).

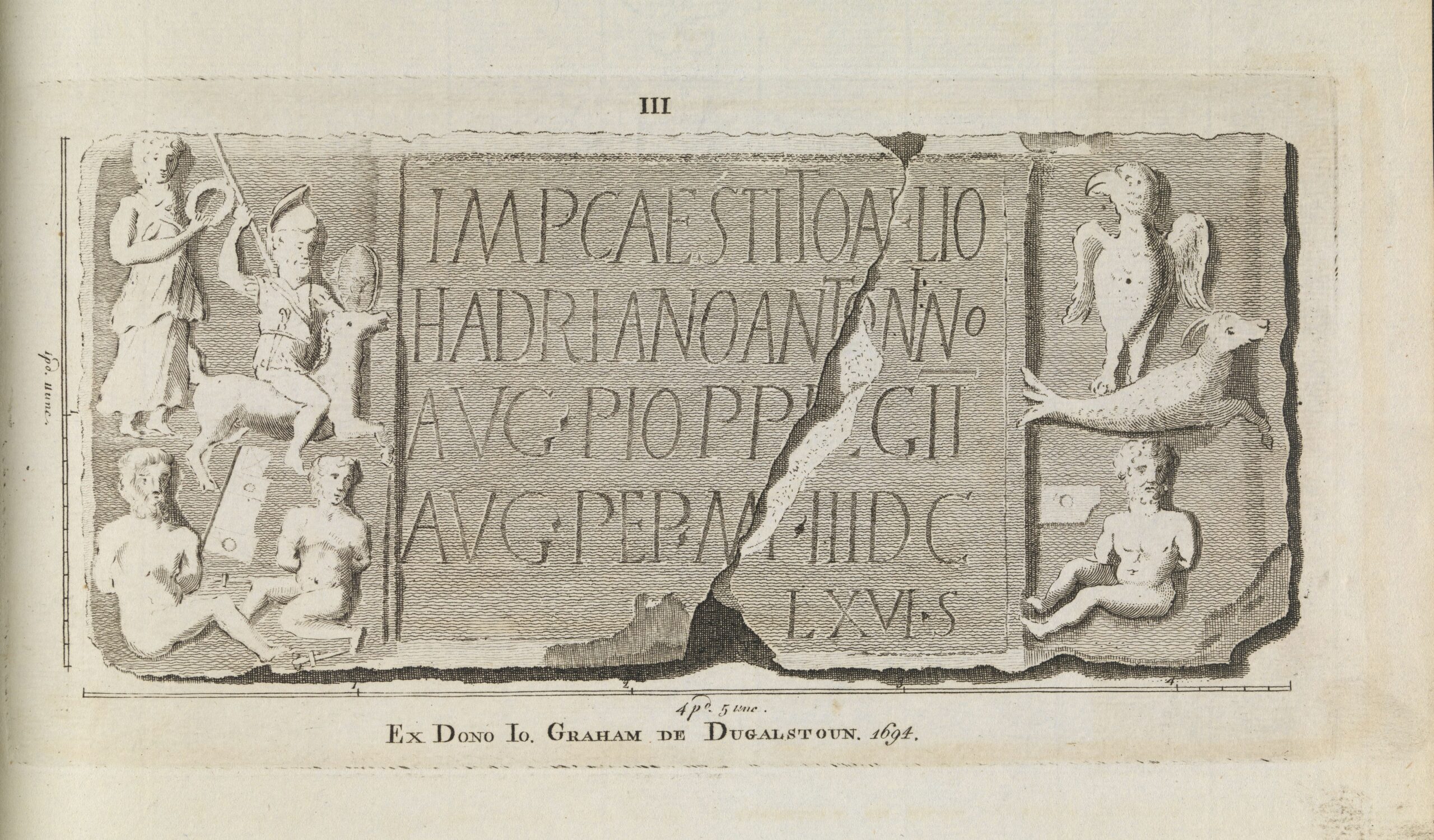

A great demonstration of the latter is found in the Monumenta Romani Imperii (1792); a series of 20 copper engravings of the Roman Distance Stones, Roman sculptures associated with the Antonine Wall. Mostly donated by local landowners to the University of Glasgow, this Roman material is today housed in the Hunterian Museum. Great examples of publications combining the study of antiquities with publications where antiquities were framed in picturesque terms include Charles Cordiner’s Remarkable ruins, and romantic prospects of North Britain (1788-1795) as well as the colourful Remarks on local scenery and manners in Scotland during the years 1799 and 1800 (1801) by John Stoddart.

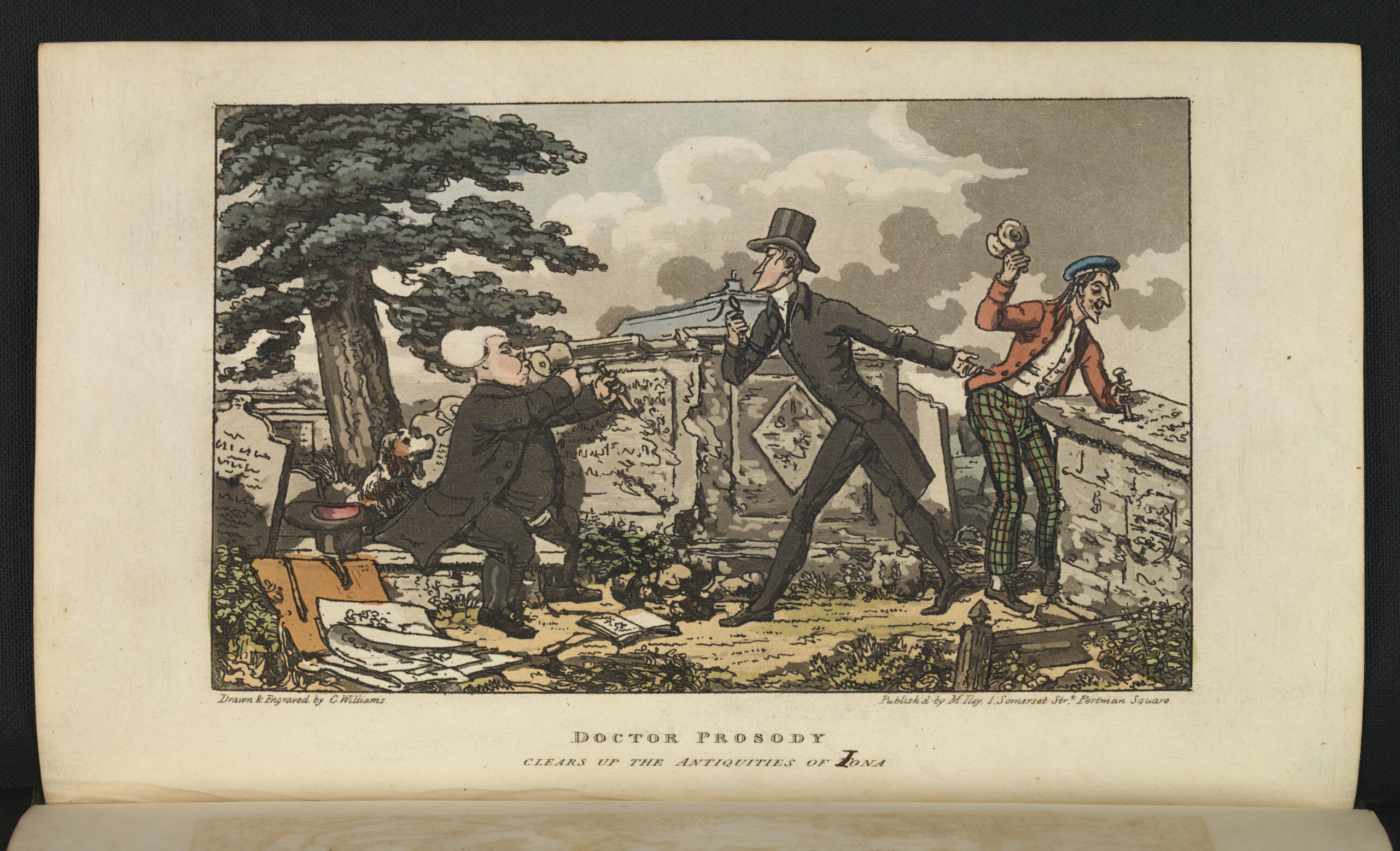

It is worth noting that all these publications can be divided into two categories. First, depictions of antiquities of a scholarly nature, like the Monumenta, fuelled by antiquarian curiosity, and second, depictions like Cordiner’s Remarkable ruins, which considered the antiquities from the point of view of tourists and travellers. It is also possible to trace a shift of interest from the Roman past to the Medieval and from there to Scottish mythology as we enter the 19th century. A constant throughout the century remains the intensity with which people looked for antiquities and picturesque landscapes, an intensity beautifully captured in one of my personal favourites, The Tour of Dr Prosody (1821) by William Combe. The book is a satirical take on the giants of the 18th century Scottish Tour, Johnson, Pennant and Gilpin. The protagonist, Dr Prosody, sets out to explore Scotland and experience the country’s natural beauty while looking for ancient ruins that can prove the authenticity of Ossian’s poems. Although he is not very successful in the latter, he does manage to entertain the reader just as he surely did 200 years ago and through satire offer us a glimpse into a century when the many faces and the multiple pasts of Scotland were opened to exploration through literature, art, and, of course, travel.