Introduction

Fieldwork and eyewitness testimony were central to furthering knowledge of the natural world. This section focuses on tours made to uncover and record Scotland’s rich mineral wealth, flora and fauna. Taking us to botanic gardens and the meeting rooms of learned societies as well as sites ‘in the field’, the texts and images gathered here also allow us to explore the collection, ordering and display of Scotland’s natural history.

Mapping Scotland’s natural environment

During the second half of the 18th-century, the wealth of specimens deposited in educational institutions, together with the tour narratives, reports, pictures and publications produced by explorers and men of science provides material evidence of the systematic exploration of the most remote corners of North Britain as they become more accessible.

Natural history, its economic potential and the building of specimen collections took pride of place as motives. While the explorers were often self-funded, the men of science tended to be supported by the state as well as educational institutions such as the Universities of Edinburgh or Glasgow or else bodies such as the Royal Society. Among those, the Royal Botanical Garden in Edinburgh and the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow were key in the formation of collections showcasing Scotland’s rich mineral wealth, flora and fauna.

Staffa

Staffa, a tiny uninhabited island off the west coast of Mull, is a geological wonder, famous for its great basalt columns and flanking sea caves. The first published account of the island dates from the late summer of 1772. Its author was the naturalist Joseph Banks who, together with his party including an astronomer, surveyor and three draughtsmen, explored Staffa on his way to Iceland via the Western Isles of Scotland.

Thomas Pennant, who had been prevented from landing on Staffa because of poor weather a few weeks earlier, published extracts from Banks’ journal together with a selection of engravings after drawings made on the spot in his 1772 Tour of Scotland.

Clearly indicative of the volcanic origin of the island, they brought Staffa to the attention of scientists involved in contemporary debates around the formation of the earth. The presence on the island of a cave that became associated with Fingal also ensured that the isle would exert a magnetic pull on the imagination of artists, composers, writers and tourists.

Hutton’s Theory of the Earth

James Hutton was a Scottish geologist, experimental agriculturalist and natural historian. His study of the Scottish landscape revolutionised the understanding of the age of the Earth. Between 1785 and 1788, Hutton travelled extensively through Scotland. Sites such as Salisbury Crags near Edinburgh and Glen Tilt in the Cairngorm mountains were crucial to his study of the long-term natural processes influencing the formation of the landscape. He was accompanied on his travels by his friend John Clerk of Eldin, whose drawings testify to their belief that accurate pictures could convey information better than words.

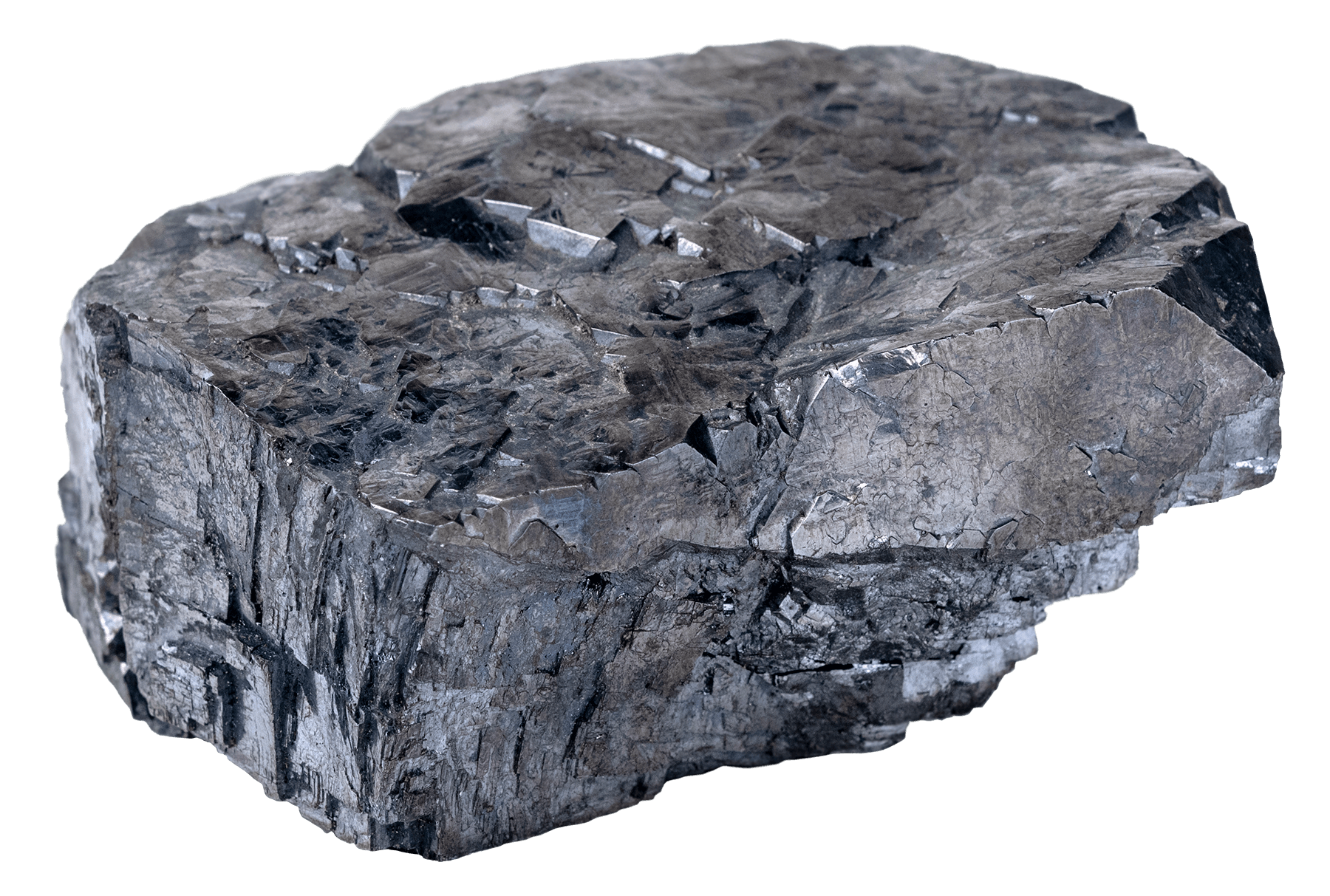

The small selection of drawings shown here – accompanied by samples of minerals from Glen Tilt collected in the late 18th century – combine different approaches to convey Hutton’s observations effectively. While they were produced for the illustration of his theories, Hutton was only able to reproduce a small selection of these drawings when he published his magnus opus The Theory of the Earth in 1788, or even the two-volume edition of 1795.

Exploiting nature’s riches

With the rapid expansion of industry in Scotland, landowners were increasingly driven to explore potential mining prospects on their estates. The country’s diversity of minerals, the rarity of some, and their quality were of particular interest to ‘gentlemen adventurers’ as well as men of science. The selection of minerals from the 18th and early 19th-century mine workings at Leadhills–Wanlockhead, Tyndrum, Strontian, Iona and Tiree included here highlight some of the stories behind the long and complex history of Scottish mines and mining in the period.